A genetically programmed action pattern is the ethologist’s definition of instinct, a complex and fascinating aspect of animal behavior. Ethology, the study of animal behavior in natural settings, delves into the intricate interplay between genetics and environment, revealing how innate behaviors are shaped and modified. From the intricate courtship dances of birds to the complex social hierarchies of primates, these genetically programmed actions, often referred to as fixed action patterns, are fundamental to understanding the diverse and captivating world of animal behavior.

These patterns, often triggered by specific stimuli, are inherited and executed with remarkable consistency, showcasing the power of genetic programming in shaping animal behavior. Understanding these patterns not only provides insight into the inner workings of animal minds but also offers valuable tools for animal welfare, conservation, and even our own understanding of human behavior.

Ethology

Ethology is the scientific study of animal behavior, focusing on understanding how animals behave in their natural environments. It delves into the evolutionary and biological underpinnings of animal actions, seeking to unravel the complex interplay of genes, environment, and experience that shapes behavior. Ethologists aim to decipher the “why” behind animal actions, exploring the adaptive significance of behaviors and their role in survival and reproduction.

Historical Development of Ethology

Ethology has a rich history, with pioneering researchers laying the groundwork for our understanding of animal behavior.

- Early Observations: Early naturalists, like Aristotle, made detailed observations of animal behavior, laying the foundation for the study of animal behavior. However, it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that ethology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline.

- The Founding Fathers: The field of ethology truly blossomed with the work of three key figures:

- Konrad Lorenz: Known for his work on imprinting, a critical learning period in young animals, Lorenz observed that goslings would follow the first moving object they saw after hatching, whether it be their mother or a human. This groundbreaking research highlighted the importance of early experiences in shaping behavior.

- Nikolaas Tinbergen: Tinbergen’s work focused on the concept of fixed action patterns (FAPs), instinctive behaviors triggered by specific stimuli. He studied the herring gull’s behavior of pecking at a red spot on its parent’s beak, a FAP that elicits food delivery. Tinbergen’s work emphasized the interplay of innate and learned behaviors.

- Karl von Frisch: Von Frisch’s research on honeybee communication revolutionized our understanding of animal communication. He discovered that bees use a “waggle dance” to communicate the location of food sources to other bees in the hive. This complex form of communication highlights the intricate social structures and communication abilities of animals.

- Ethology’s Legacy: The work of Lorenz, Tinbergen, and von Frisch earned them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973, solidifying ethology’s place as a crucial discipline in the study of animal behavior. Their pioneering research established the foundations for modern ethological research, emphasizing the importance of studying behavior in natural settings and considering the evolutionary and adaptive significance of animal actions.

Ethological Research and its Contributions

Ethological research has yielded a wealth of insights into the diverse world of animal behavior, contributing to our understanding of animal cognition, social interactions, and evolutionary adaptations.

- Animal Cognition: Ethologists have demonstrated the surprising cognitive abilities of animals, challenging the notion that humans are the only species capable of complex thought. Studies on chimpanzees, for example, have shown that they possess the capacity for tool use, problem-solving, and even rudimentary language. These findings have challenged our understanding of animal intelligence and raised questions about the evolution of cognition.

- Social Interactions: Ethological research has shed light on the intricate social structures and interactions found in animal societies. From the complex hierarchies of wolf packs to the cooperative breeding strategies of meerkats, ethologists have uncovered the fascinating ways in which animals interact with each other, revealing the importance of social bonds in survival and reproduction.

- Evolutionary Adaptations: Ethological research has played a crucial role in understanding the evolutionary basis of behavior. By studying the adaptive significance of behaviors in different environments, ethologists have uncovered the intricate ways in which animals have evolved to thrive in their specific ecological niches. For example, the migration patterns of birds, the camouflage strategies of insects, and the hunting techniques of predators are all examples of evolutionary adaptations that have been shaped by natural selection.

Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Imagine a newborn baby bird, just hatched from its egg. It’s never seen the sky, felt the wind, or heard the chirping of its parents. Yet, within minutes, it instinctively knows how to open its beak and beg for food. This innate ability, present from birth, is a prime example of a genetically programmed action pattern, also known as a fixed action pattern.

These patterns are pre-wired behaviors, encoded in an animal’s genes, guiding its actions and shaping its behavior.

The Role of Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Genetically programmed action patterns are the foundation of an animal’s behavioral repertoire. They are crucial for survival, ensuring that essential actions like finding food, escaping predators, and reproducing are carried out effectively. These patterns are often triggered by specific stimuli, called releasers. For instance, a red dot on a male stickleback fish’s belly triggers an aggressive response in other males, protecting its territory.

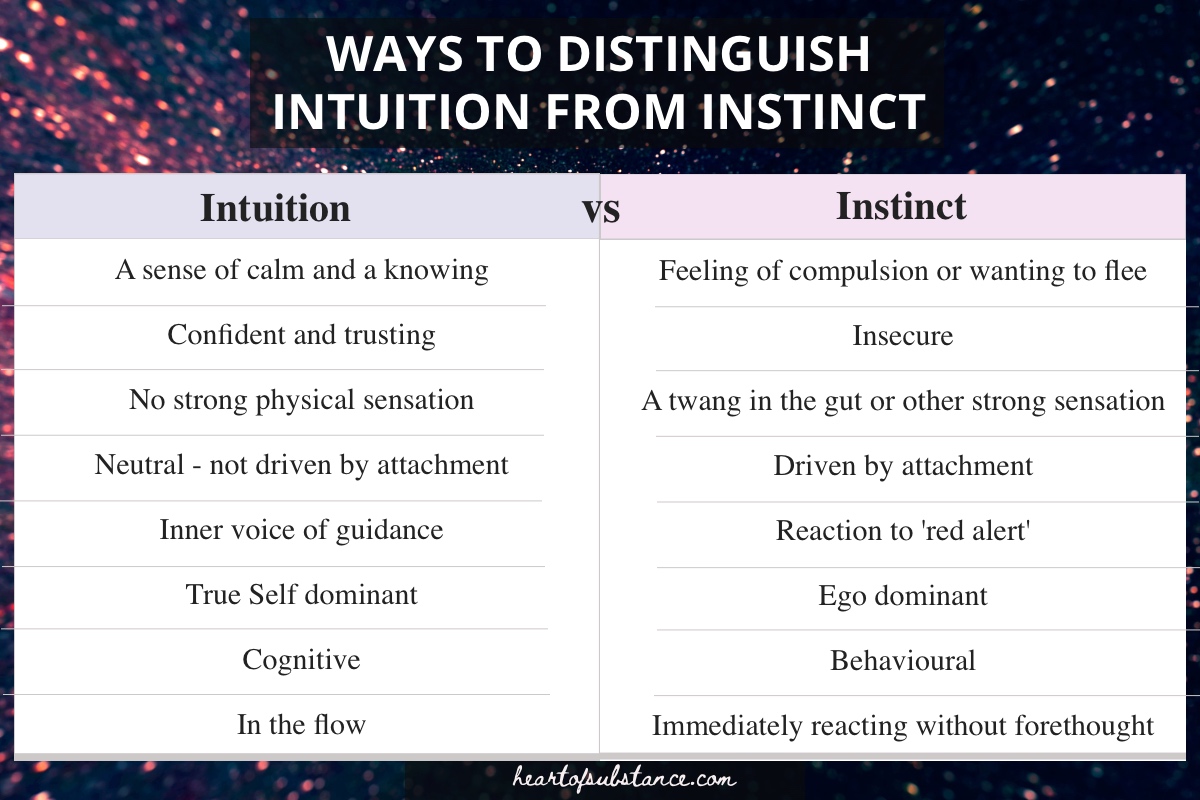

Instinct and Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Instinct, a complex concept, is often intertwined with genetically programmed action patterns. It refers to innate behaviors, often described as unlearned and automatic responses to specific stimuli. While instinct encompasses a broader range of behaviors, genetically programmed action patterns are considered the core building blocks of instinctual behavior.

Examples of Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

- Web building in spiders: Spiders, like the orb weaver, are born with the blueprint for constructing intricate webs. They don’t learn this skill; it’s genetically encoded in their DNA, enabling them to build complex webs from the moment they hatch.

- Migration in birds: Many bird species, like the Arctic tern, migrate thousands of miles each year. This instinctual behavior is guided by internal biological clocks, celestial cues, and a genetically programmed sense of direction, ensuring they reach their breeding and feeding grounds.

- Suckling in mammals: Newborn mammals, including humans, instinctively know how to find their mother’s nipple and suckle for nourishment. This behavior is crucial for survival and is triggered by the mother’s scent and the baby’s need for food.

- Courtship displays in birds: Birds like the blue-footed booby perform elaborate courtship dances, involving specific movements and calls. These displays are genetically programmed and serve to attract mates, ensuring successful reproduction.

Types of Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Genetically programmed action patterns (GPAPs) are innate, unlearned behaviors that are triggered by specific stimuli. These patterns are essential for survival, reproduction, and overall well-being in many species. While GPAPs are often described as “instinctive” or “hardwired,” they can be influenced by environmental factors and learning experiences.

Fixed Action Patterns

Fixed action patterns (FAPs) are complex, stereotyped sequences of behaviors that are typically triggered by a specific sign stimulus. FAPs are often described as “all-or-nothing” responses, meaning that once initiated, they are usually carried out to completion regardless of external factors.

FAPs are characterized by their unlearned nature, stereotyped sequence, and completion even if the triggering stimulus is removed.

Here are some examples of FAPs in the animal kingdom:

- Greylag goose egg retrieval: When a greylag goose sees an egg outside of its nest, it will roll the egg back into the nest using its beak. This behavior is triggered by the visual stimulus of an egg outside the nest and will continue even if the egg is removed during the process.

- Stickleback fish courtship behavior: Male stickleback fish display a series of elaborate courtship behaviors, including a zig-zag dance, to attract females. These behaviors are triggered by the presence of a female stickleback fish and are essential for successful reproduction.

- The red belly of a male stickleback fish triggering aggression: When a male stickleback fish sees a red belly, it will attack the perceived rival. This is a clear example of a FAP, as the male stickleback fish will attack anything with a red belly, even inanimate objects.

The Role of Environment in Shaping Behavior

While genetically programmed action patterns provide a foundation for behavior, the environment plays a crucial role in shaping how these patterns are expressed. It’s like having a blueprint for a house, but the actual construction and the final look depend on the materials, tools, and the landscape it’s built on.

Environmental Triggers for Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Environmental factors can act as triggers, activating or modifying genetically programmed action patterns. Think of it like a switch that turns on a pre-programmed behavior. For instance, the sight of a predator can trigger a flight response in a prey animal, even if the animal has never encountered a predator before. This is because the flight response is a genetically programmed action pattern that is triggered by specific environmental cues.

Environmental Influences on the Expression of Behavior

Environmental factors can also influence the expression of behavior by shaping the development of an individual’s nervous system. This means that the environment can change how the brain processes information and responds to stimuli.

- Learning: Learning is a prime example of how the environment shapes behavior. Through experience, animals can acquire new behaviors or modify existing ones. For example, a bird may learn to avoid a particular type of food after experiencing a negative consequence.

- Socialization: Social interactions play a significant role in shaping behavior, especially in social species. For instance, a young wolf may learn hunting techniques from its pack members.

- Cultural Transmission: In some species, behaviors can be passed down through generations, not just through genes, but through learning and imitation. This is called cultural transmission. For example, chimpanzees in different communities have distinct ways of using tools, which are passed down through generations.

Examples of Environmental Influence on Behavior, A genetically programmed action pattern is the ethologist’s definition of

Here are some examples of how environmental factors can influence the expression of specific behaviors:

- Bird Song: The song of a male bird is a complex behavior that is influenced by both genes and the environment. While the basic structure of the song is genetically determined, the specific variations in the song are learned from other birds. For example, a young bird raised in isolation will sing a song that is different from the song of birds raised in a social group.

- Nest Building: Birds have a genetically programmed action pattern to build nests. However, the specific materials used and the shape of the nest can vary depending on the environment. For example, birds living in areas with abundant twigs may build larger, more elaborate nests than birds living in areas with limited resources.

- Foraging Behavior: Foraging behavior is influenced by both genetic predisposition and environmental factors. For example, a squirrel may have a genetic predisposition to bury nuts, but the specific locations where it buries the nuts will be influenced by the availability of suitable hiding spots.

Evolutionary Significance of Genetically Programmed Action Patterns

Genetically programmed action patterns, also known as fixed action patterns, play a crucial role in the survival and reproductive success of animals. These innate behaviors, shaped by natural selection over generations, contribute to the fitness of individuals and their species.

Evolutionary Origins and Adaptive Value of Action Patterns

The evolutionary origins of action patterns are rooted in the interplay between genetic inheritance and environmental pressures. Natural selection favors traits that enhance survival and reproduction, and action patterns are no exception.

- Survival: Action patterns can help animals obtain essential resources like food, shelter, and mates. For example, the hunting behaviors of predators, such as the stalking and ambush tactics of a lion, are genetically programmed to maximize their chances of securing prey.

- Reproduction: Many action patterns are directly involved in courtship and mating rituals, ensuring successful reproduction. The elaborate mating dances of birds, like the peacock’s display of its tail feathers, are genetically programmed behaviors that attract potential mates.

- Defense: Action patterns can also provide protection against predators. The defensive displays of some animals, such as the hissing of a cat or the warning coloration of a poisonous frog, serve as deterrents to potential threats.

Examples of Action Patterns Evolving in Response to Environmental Pressures

- Migration: Birds migrating long distances rely on genetically programmed navigation abilities, which have evolved over time to ensure they reach suitable breeding grounds. The internal compass of birds, which utilizes the Earth’s magnetic field, is a prime example of a genetically programmed action pattern that has been refined by natural selection.

- Camouflage: The camouflage patterns of animals, such as the stripes of a zebra or the spots of a leopard, are genetically programmed adaptations that help them blend into their surroundings, reducing their vulnerability to predators.

- Social Behavior: Complex social behaviors, such as the cooperative hunting strategies of wolves or the intricate social hierarchies of primates, are also influenced by genetically programmed action patterns. These behaviors, honed over generations, have evolved to optimize group cohesion and survival.

Applications of Ethological Knowledge

Ethology, the study of animal behavior in their natural environment, has moved beyond mere observation and into the realm of practical applications. Understanding genetically programmed action patterns, or instincts, has proven invaluable in various fields, from animal husbandry to conservation and wildlife management.

Animal Husbandry

Ethological knowledge is crucial for optimizing animal welfare and productivity in agricultural settings. By understanding the natural behaviors and needs of livestock, farmers can design more humane and efficient practices. For example, understanding the social dynamics of chickens can help farmers create housing arrangements that reduce stress and aggression, leading to improved egg production. Similarly, recognizing the grazing patterns of cattle can inform the design of pasture management strategies that promote natural foraging behaviors and reduce the risk of overgrazing.

The study of genetically programmed action patterns in ethology offers a window into the remarkable complexity of animal behavior. By understanding the interplay between genetics, environment, and these innate patterns, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity and sophistication of animal life. This knowledge not only enhances our understanding of the natural world but also informs our interactions with animals, leading to more humane and effective approaches to animal welfare, conservation, and even the study of our own species.

Quick FAQs: A Genetically Programmed Action Pattern Is The Ethologist’s Definition Of

What are some examples of genetically programmed action patterns?

Examples include a bird building a nest, a spider spinning a web, a baby sucking on a nipple, and a dog wagging its tail.

How can environmental factors influence genetically programmed action patterns?

Environmental factors can trigger or modify genetically programmed action patterns. For example, the presence of a predator can trigger a flight response in a prey animal, while the absence of food can lead to a foraging behavior.

What is the evolutionary significance of genetically programmed action patterns?

Genetically programmed action patterns contribute to the survival and reproductive success of animals. They are often adaptive responses to specific environmental challenges and can help animals find food, avoid predators, and reproduce successfully.