How to obtain stroma-free hemoglobin is a question that has captivated researchers and scientists for decades. Stroma-free hemoglobin, a purified form of the oxygen-carrying protein found in red blood cells, holds immense potential in various fields, from medicine to biotechnology. This guide delves into the intricacies of obtaining this valuable biomolecule, exploring the traditional methods, modern techniques, and future directions in this exciting area of research.

The journey to obtain stroma-free hemoglobin involves a meticulous process that begins with the extraction of hemoglobin from red blood cells. This extraction process, often involving sophisticated techniques like lysis and centrifugation, aims to isolate the hemoglobin molecule while removing the cellular debris, or stroma. Once extracted, the hemoglobin must be purified further to remove any remaining contaminants and ensure its stability and functionality.

This purification step often involves techniques like chromatography and filtration, which selectively separate the desired hemoglobin from other molecules.

Introduction to Stroma-Free Hemoglobin

Stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH) is a purified form of hemoglobin that has been stripped of its cellular membrane, known as the stroma. This process removes extraneous components, such as lipids, proteins, and other cellular debris, resulting in a concentrated solution of pure hemoglobin.SFH offers several advantages over whole blood, making it a valuable tool in various medical and research applications. It is a stable and readily available source of oxygen-carrying capacity, crucial for its diverse uses.

Applications of Stroma-Free Hemoglobin

The unique properties of SFH have led to its application in various fields, including:

- Blood Substitutes: SFH has been explored as a potential blood substitute, particularly in emergency situations where blood transfusions are unavailable or impractical. Its oxygen-carrying capacity can temporarily compensate for blood loss, offering a lifeline in critical scenarios.

- Drug Delivery: SFH’s ability to bind and transport molecules has made it a promising candidate for targeted drug delivery. By attaching therapeutic agents to SFH, researchers aim to deliver drugs directly to specific tissues or organs, enhancing efficacy and minimizing side effects.

- Tissue Engineering: SFH plays a vital role in tissue engineering, particularly in the development of artificial blood vessels and other engineered tissues. Its oxygen-carrying capacity promotes cell growth and survival, facilitating the formation of functional tissues.

- Biomedical Research: SFH serves as a valuable tool in biomedical research, enabling scientists to study the mechanisms of oxygen transport and its role in various biological processes. It is used in cell culture studies, animal models, and other research endeavors.

Methods for Obtaining Stroma-Free Hemoglobin

Obtaining stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH) is a crucial step in various biomedical applications, particularly in blood substitutes and oxygen therapies. The process involves separating hemoglobin from red blood cell membranes (stroma) to create a purified and functional hemoglobin solution. This section explores traditional methods for obtaining SFH, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages.

Traditional Methods for Obtaining Stroma-Free Hemoglobin

Traditional methods for obtaining SFH primarily rely on disrupting the red blood cell membrane to release hemoglobin. These methods have been widely employed, but they often face challenges related to efficiency, cost, and potential side effects.

- Hypotonic Lysis: This method involves placing red blood cells in a hypotonic solution, which causes water to enter the cells and swell, ultimately leading to membrane rupture. This releases hemoglobin into the solution.

- Freezing and Thawing: This method involves freezing red blood cells, which disrupts the cell membrane during the thawing process. Hemoglobin is then released into the solution.

- Detergent Lysis: Detergents like Triton X-100 are used to disrupt the cell membrane, releasing hemoglobin. This method is known for its efficiency, but it can also lead to the denaturation of hemoglobin if not carefully controlled.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Traditional Methods

Traditional methods for obtaining SFH have advantages and disadvantages that influence their applicability and effectiveness.

- Hypotonic Lysis:

- Advantages: Relatively simple and inexpensive method.

- Disadvantages: Can result in significant hemoglobin degradation, leading to lower yields and reduced functional activity.

- Freezing and Thawing:

- Advantages: Can be performed in large batches and is relatively inexpensive.

- Disadvantages: Can lead to hemoglobin aggregation and denaturation, reducing its efficacy.

- Detergent Lysis:

- Advantages: High efficiency in releasing hemoglobin.

- Disadvantages: Potential for hemoglobin denaturation and the need for extensive purification steps to remove detergent residues.

Comparison of Traditional Methods

The efficiency and cost-effectiveness of traditional methods for obtaining SFH vary significantly.

- Hypotonic lysis is generally considered the least efficient and cost-effective method due to its low yield and potential for hemoglobin degradation.

- Freezing and thawing offers a moderate level of efficiency but can be prone to hemoglobin denaturation, making it less ideal for large-scale production.

- Detergent lysis is the most efficient method but requires extensive purification steps to remove detergent residues, leading to increased costs.

Hemoglobin Extraction Techniques

Extracting hemoglobin from red blood cells is a crucial step in obtaining stroma-free hemoglobin. This process involves disrupting the red blood cell membrane to release hemoglobin while minimizing damage to the hemoglobin molecule itself. Several techniques have been developed to achieve this, each with its advantages and disadvantages.

Hemolysis Techniques

Hemolysis refers to the rupture of red blood cells, releasing their contents, including hemoglobin. Various methods can be employed to induce hemolysis, each relying on different mechanisms to disrupt the cell membrane.

- Osmotic Hemolysis: This technique utilizes the principle of osmotic pressure. Red blood cells are placed in a hypotonic solution, a solution with a lower concentration of solutes than the cell’s cytoplasm. Water moves into the cells, causing them to swell and eventually burst, releasing hemoglobin.

- Freezing and Thawing: Repeated freezing and thawing of red blood cells can disrupt the cell membrane. This method is often used in combination with other techniques to enhance hemolysis.

- Sonication: Ultrasound waves can be used to disrupt the cell membrane by generating cavitation bubbles that collapse, creating mechanical stress on the cells. This method is efficient but can also cause damage to the hemoglobin molecule.

- Chemical Hemolysis: Various chemicals can be used to disrupt the cell membrane. These include detergents, such as Triton X-100, which solubilize the membrane lipids, and organic solvents, such as chloroform, which extract lipids from the membrane.

Stroma Removal Techniques

Stroma removal is a crucial step in the production of stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH). The stroma, which is the membrane-bound structure that encloses the red blood cell, contains various components, including lipids, proteins, and enzymes, that can interfere with the therapeutic efficacy and stability of hemoglobin. Removing the stroma is essential to obtain pure hemoglobin for medical applications.

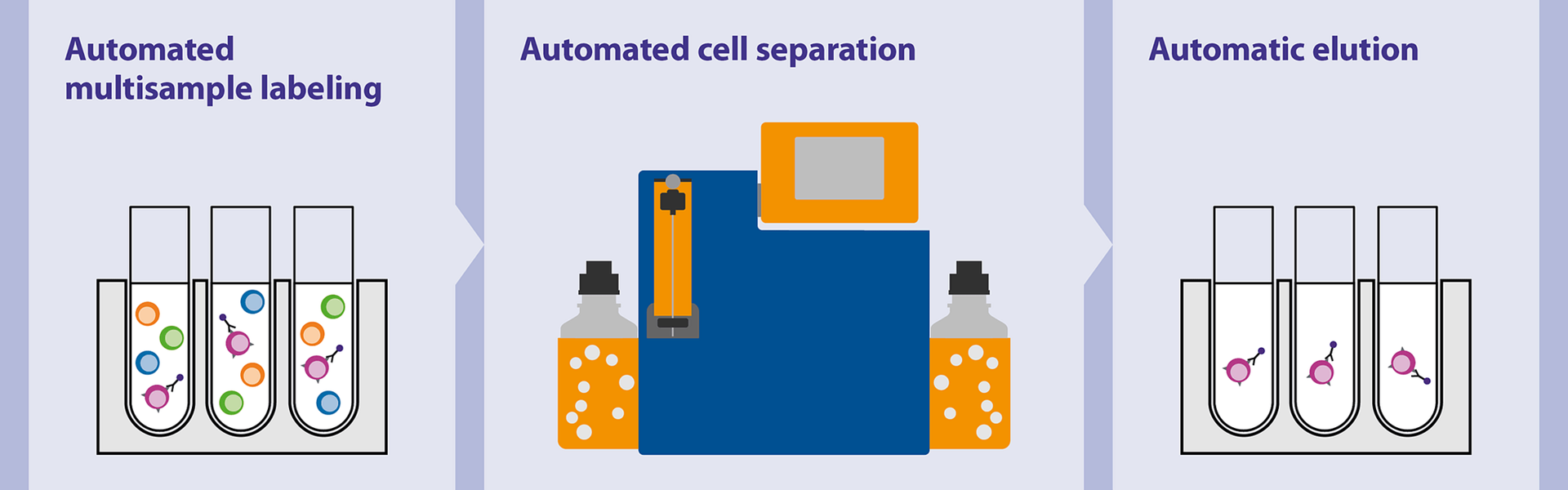

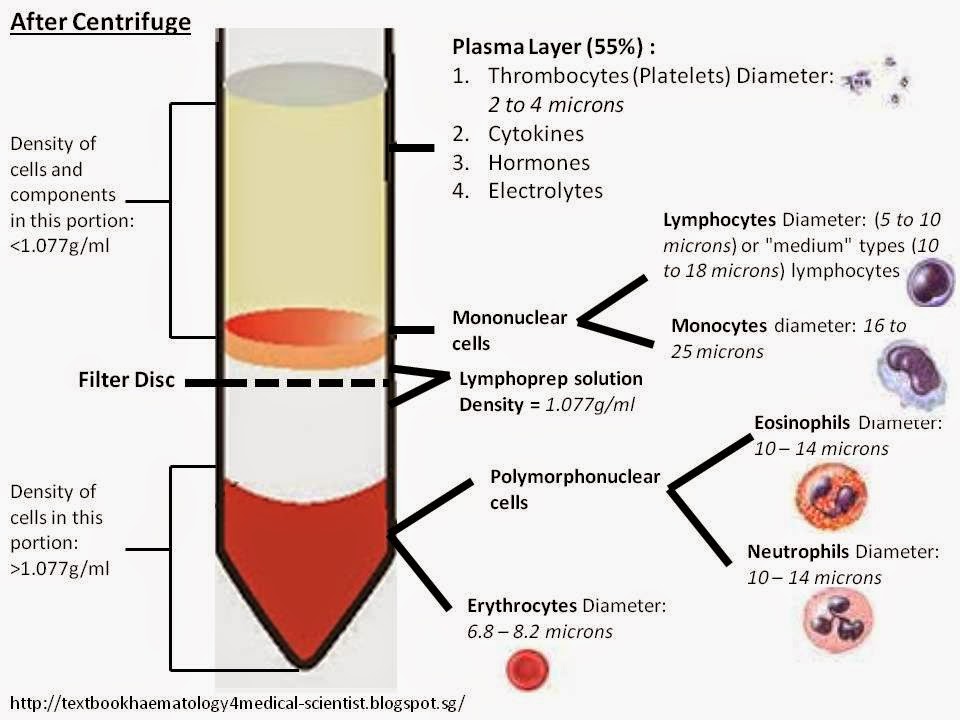

Hemolysis and Centrifugation

Hemolysis, the breakdown of red blood cells, is the initial step in stroma removal. This process releases hemoglobin from the red blood cells, leaving behind the stroma. Hemolysis can be achieved through various methods, including osmotic shock, freezing, and sonication. After hemolysis, the solution is centrifuged to separate the stroma from the hemoglobin. The heavier stroma settles at the bottom of the centrifuge tube, while the hemoglobin remains in the supernatant.

The effectiveness of this technique depends on the efficiency of hemolysis and the centrifugation parameters.

Differential Filtration

Differential filtration uses filters with different pore sizes to separate stroma from hemoglobin. The stroma, which is larger than hemoglobin, is retained by the filter, while the smaller hemoglobin molecules pass through. This technique is commonly used for large-scale production of SFH.

The pore size of the filter is crucial for efficient stroma removal, as it must be small enough to retain the stroma but large enough to allow the passage of hemoglobin.

Affinity Chromatography

Affinity chromatography utilizes the specific binding affinity of hemoglobin to certain ligands to separate it from the stroma. This method involves attaching a ligand that binds to hemoglobin to a solid support, such as a resin. The hemoglobin solution is then passed through the column, and the hemoglobin binds to the ligand, while the stroma passes through.

The effectiveness of this technique depends on the specificity and strength of the ligand-hemoglobin interaction.

Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration is a membrane-based separation technique that utilizes a semi-permeable membrane to separate molecules based on their size. The stroma, which is larger than hemoglobin, is retained by the membrane, while the smaller hemoglobin molecules pass through.

The pore size of the ultrafiltration membrane is crucial for efficient stroma removal.

Enzymatic Digestion

Enzymatic digestion utilizes enzymes to break down the stroma. This method involves treating the hemolyzed red blood cell solution with enzymes that specifically degrade the stroma components. The digested stroma is then removed by filtration or centrifugation.

The choice of enzyme and the digestion conditions are critical for efficient stroma removal without affecting the hemoglobin molecule.

Characterization of Stroma-Free Hemoglobin: How To Obtain Stroma-free Hemoglobin

The quality and suitability of stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH) for specific applications hinge on its characterization. This involves a thorough assessment of its purity, stability, and functionality. Various methods are employed to analyze these key parameters, ensuring that the extracted SFH meets the desired criteria for its intended use.

Purity Assessment

Determining the purity of SFH is crucial to ensure that it is free from contaminants that could compromise its efficacy and safety. Several techniques are used to assess the purity of SFH, including:

- Spectrophotometry: This method measures the absorbance of light by the SFH solution at specific wavelengths. The absorbance spectrum of pure SFH is distinct and can be used to identify and quantify any contaminating proteins or other molecules.

- Electrophoresis: This technique separates proteins based on their size and charge. SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) is commonly used to assess the purity of SFH by separating it from other proteins present in the sample.

- Chromatography: This technique separates molecules based on their affinity for a stationary phase. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and ion-exchange chromatography (IEC) are frequently employed to purify and characterize SFH, separating it from other molecules based on their size and charge.

Stability Evaluation

The stability of SFH is paramount, as it determines its shelf life and ability to retain its functionality over time. Factors such as temperature, pH, and the presence of oxygen can affect the stability of SFH.

- Thermal Stability: The ability of SFH to withstand heat is assessed by monitoring its degradation at different temperatures. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a common technique used to measure the thermal stability of SFH.

- pH Stability: The stability of SFH at different pH values is crucial for its storage and application. The pH range over which SFH remains stable is determined by monitoring its degradation at different pH values.

- Oxidative Stability: The susceptibility of SFH to oxidation is evaluated by monitoring its degradation in the presence of oxygen. Techniques such as spectrophotometry and mass spectrometry are used to measure the extent of oxidation.

Functionality Assessment

The functionality of SFH refers to its ability to bind and transport oxygen. This is a critical aspect for its use as a blood substitute.

- Oxygen Binding Capacity: This measures the amount of oxygen that SFH can bind per unit of hemoglobin. This is typically determined using a spectrophotometer and a known concentration of SFH.

- Oxygen Affinity: This measures the strength of the bond between SFH and oxygen. It is determined by measuring the partial pressure of oxygen at which SFH is 50% saturated with oxygen (P50).

- Redox Properties: The ability of SFH to undergo reversible oxidation and reduction is crucial for its oxygen-carrying capacity. This is assessed by measuring its redox potential and its ability to bind and release oxygen.

Suitability for Specific Applications

The suitability of SFH for specific applications depends on its characteristics and the requirements of the application.

- Blood Substitute: For use as a blood substitute, SFH must possess high oxygen-carrying capacity, stability in physiological conditions, and minimal toxicity.

- Drug Delivery: SFH can be used as a carrier for drug delivery, especially for oxygen-sensitive drugs. Its ability to bind and release oxygen can be utilized to deliver drugs to specific tissues.

- Biomaterials: SFH can be incorporated into biomaterials to improve their oxygen-carrying capacity and biocompatibility. This can be particularly useful for applications in tissue engineering and wound healing.

Applications of Stroma-Free Hemoglobin

Stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH) is a versatile molecule with numerous applications in various fields, including medicine, biotechnology, and industry. It is a modified form of hemoglobin that has been stripped of its cellular membrane and other extraneous proteins, making it a highly pure and stable form of oxygen carrier.

Medical Applications

SFH has significant potential in medical applications due to its oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Blood Substitutes: SFH is being investigated as a potential blood substitute for patients who have lost significant blood volume due to trauma or surgery. It can temporarily replace red blood cells and deliver oxygen to tissues, reducing the need for blood transfusions. For example, the product Hemopure, developed by Biopure, was investigated as a blood substitute for patients undergoing surgery or suffering from acute anemia.

- Treatment of Anemia: SFH can be used to treat anemia, a condition characterized by a deficiency of red blood cells or hemoglobin. It can provide oxygen to tissues, improving symptoms such as fatigue and shortness of breath. One example is the use of SFH in patients with sickle cell anemia, where it can temporarily reduce the need for blood transfusions and alleviate symptoms.

- Drug Delivery: SFH can be used as a drug delivery vehicle, carrying therapeutic agents to specific tissues or organs. This is because SFH can be modified to bind to specific drugs and target them to the desired location. For example, SFH has been used to deliver anticancer drugs to tumors, improving their efficacy and reducing side effects.

Biotechnology Applications

SFH finds applications in biotechnology due to its ability to bind and transport oxygen.

- Oxygen Scavenging: SFH can be used to remove oxygen from biological samples, such as cell cultures or fermentation processes. This is crucial for maintaining anaerobic conditions, which are essential for the growth of certain microorganisms or the preservation of sensitive biological materials. For example, SFH is used in the production of biofuels, where it helps to remove oxygen from the fermentation process, improving the yield of bioethanol.

- Biomedical Research: SFH is a valuable tool in biomedical research, enabling the study of oxygen transport and metabolism. It is used in experiments to investigate the effects of oxygen deprivation on cells and tissues, providing insights into various physiological processes.

Industrial Applications

SFH also finds applications in various industries, including food processing and environmental remediation.

- Food Preservation: SFH can be used as a natural preservative in food products, extending their shelf life and preventing spoilage. It acts as an oxygen scavenger, inhibiting the growth of microorganisms that cause food deterioration. For example, SFH is used in the packaging of meat products to extend their shelf life and maintain freshness.

- Environmental Remediation: SFH can be used to remove pollutants from the environment, such as heavy metals or organic contaminants. It can bind to these pollutants, facilitating their removal from soil or water. For example, SFH has been investigated for its ability to remove arsenic from contaminated water sources.

Future Directions in Stroma-Free Hemoglobin Research

While stroma-free hemoglobin (SFH) holds great promise for various medical applications, several limitations and challenges hinder its widespread adoption. Ongoing research aims to overcome these obstacles and unlock the full potential of SFH.

Improving Production and Stability

The efficient and cost-effective production of SFH remains a critical challenge. Current methods, such as hemolysis and purification, are often time-consuming and expensive. Moreover, SFH is susceptible to degradation and aggregation, limiting its shelf life and therapeutic efficacy. Future research will focus on:

- Developing novel and efficient methods for extracting and purifying hemoglobin from red blood cells, potentially utilizing enzymatic or bio-based approaches.

- Exploring new strategies for stabilizing SFH, such as modifying its structure or encapsulating it within biocompatible materials to prevent degradation and aggregation.

- Investigating the use of genetically engineered hemoglobin variants with enhanced stability and oxygen-carrying capacity.

Addressing Safety Concerns

SFH’s safety profile is a major concern, particularly its potential to cause vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, and methemoglobinemia. These concerns have limited its clinical application, necessitating further research and development. Future research will focus on:

- Investigating the mechanisms underlying SFH-induced vasoconstriction and developing strategies to mitigate this effect, such as using specific chemical modifications or co-administering vasodilators.

- Exploring the use of SFH derivatives with reduced oxidative stress potential or incorporating antioxidants to minimize oxidative damage.

- Developing methods for monitoring methemoglobin levels in patients receiving SFH therapy and implementing appropriate interventions to prevent methemoglobinemia.

Expanding Therapeutic Applications

SFH has the potential to treat a wide range of conditions, including anemia, acute blood loss, and even cancer. However, its current applications are limited due to safety concerns and lack of clinical data. Future research will focus on:

- Conducting well-designed clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of SFH in various therapeutic settings, particularly for treating acute blood loss and sickle cell disease.

- Investigating the potential of SFH as a carrier for targeted drug delivery, utilizing its oxygen-carrying capacity to deliver therapeutic agents to specific tissues or organs.

- Exploring the use of SFH in regenerative medicine, particularly in the development of bioartificial organs and tissue engineering.

Utilizing Advanced Technologies, How to obtain stroma-free hemoglobin

Emerging technologies offer exciting possibilities for improving SFH production, stability, and therapeutic applications. Future research will focus on:

- Employing bioengineering techniques to design and produce novel hemoglobin variants with enhanced properties, such as increased oxygen affinity or reduced vasoconstriction.

- Leveraging nanotechnology to develop biocompatible and biodegradable nanocarriers for encapsulating SFH, enhancing its stability and targeted delivery.

- Utilizing artificial intelligence and machine learning to accelerate drug discovery and optimize SFH production processes.

Obtaining stroma-free hemoglobin is a testament to the ingenuity and perseverance of scientists who are constantly pushing the boundaries of research. From its humble beginnings in the laboratory, this biomolecule has emerged as a powerful tool with the potential to revolutionize various industries. As we continue to explore new methods and techniques for obtaining and utilizing stroma-free hemoglobin, the future holds exciting possibilities for its applications in medicine, biotechnology, and beyond.

FAQ Overview

What are the main applications of stroma-free hemoglobin?

Stroma-free hemoglobin has a wide range of applications, including blood substitutes, oxygen delivery systems, and drug delivery vehicles. It is also used in research to study the function of hemoglobin and its role in oxygen transport.

What are the challenges associated with obtaining stroma-free hemoglobin?

Challenges include ensuring the purity and stability of the hemoglobin, minimizing the risk of contamination, and optimizing the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the extraction and purification processes.

What are the future directions in stroma-free hemoglobin research?

Future research focuses on developing new techniques for obtaining and utilizing stroma-free hemoglobin, exploring its potential for treating various diseases, and investigating its applications in advanced biomaterials and nanotechnology.